Beyond COVID-19 – ED Planning for Future Surge Events

Existing hospitals were underprepared to accommodate a sudden surge of infectious patients with so many variables: How is the virus transmitted? Who is infectious? When would peak surge occur?

Although the emergency department was at the front line of this response, the facility’s needs changed dramatically – even as the pandemic progressed. Although it was initially overrun with patients, the ED became underutilized as more people sheltered in place, and healthcare officials enforced pre-testing. While the world navigates its way through this evolving situation, with parameters that change by the day, architects, engineers, and medical systems are identifying strategies to design more agile EDs that are adaptable and responsive to a broader range of scenarios. This proactive approach could fundamentally change the way in which future EDs are designed and operated.

Our teams regularly consider future flexibility and functionality when planning a new ED. Moving forward, the highly disruptive impact of the novel coronavirus requires us to consider worst-case surge scenarios, to expand some fundamental planning assumptions, and to leverage virtual care. Because of relaxed regulations and higher reimbursements, we have witnessed the quick switch by many health systems to telemedicine. How can the future ED be designed to facilitate tele-triage and at-home monitoring as an alternative to the in-person visit? In a previous blog, we proposed and modeled a bundled set of strategies that rapidly allow an ED to meet surging inpatient and screening needs without renovation. Here, we discuss recommendations for the design and layout of a new ED to maximize safety and operational readiness during surge conditions.

Managing points of entry and circulation

- Controlled points of entry – Review all possible interior and exterior ED entry options under multiple scenarios.

- If one entry is blocked for mass screening/triage, can ambulance or behavioral health circulation still be maintained?

- Do circulation paths allow for both general access to the facility and a separate path of travel from an external testing/triage space to the appropriate treatment area.

- Consider adding control points (card- access) at strategic locations within the ED to reinforce appropriate traffic patterns and limit exposure by non-essential staff.

- Separation of traffic paths – Analyze the path of travel for public vs. service and clean vs. dirty to identify opportunities to separate traffic and minimize cross-contamination. This includes horizontal traffic (corridors), vertical traffic (elevators), and general access through the hospital.

Creating EDs within the ED

- Pod layouts – For larger EDs, employ multiple pods of negative-pressure treatment rooms to provide containment of infectious patients and flexibility for various acuity levels.

- Separate patients by acuity – Examine options to treat low-acuity and non-surge patients separately during a disaster.

Additional capacity

- Soft Space - Locate other “soft space” (administrative or non-clinical) adjacent to the ED for adaptable uses in the short term, to accommodate beds, staging areas, or other displaced spaces. Larger conference spaces and cafeterias could be used for lower acuity patients, with more serious cases going to the ED.

- External expansion zone - Plan adjacent space (such as parking garages, canopied areas, or open space) for temporary conversion to mass screening, testing, triage, or decontamination use. Provide infrastructure including water, power, and telecommunications that is secure and available for immediate use. If possible, plan for drive-thru capability for high thru-put processes.

- Repurpose space - If an observation unit is located adjacent to the Emergency Department this is an opportunity for quick expansion of ED capacity. Relocating patients to other medical floors may be another option to free up space in the ED. Alternatively, if ED visits are lower, a negative pressure pod could be repurposed for less acute, infectious inpatients.

- Telemedicine – The widespread adaptation of telemedicine for outpatient care may have some corollary use in the ED. Lower acuity patients could get triaged remotely – and either stay home or be referred to an alternate location. Physical space would not be necessary within the ED department.

Some planning and regulatory fundamentals that are typical in other clinical areas may have new relevance in the emergency department.

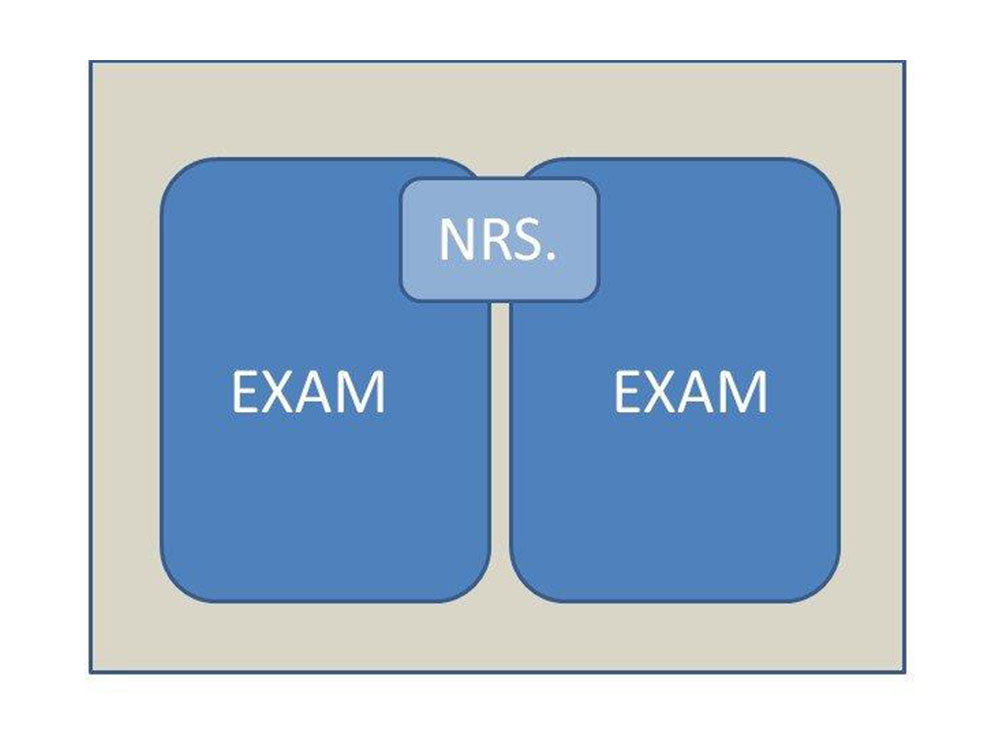

Decentralized workspaces – Add workspace at the entry to pairs of exam rooms to allow patient observation in a protected zone. This can be accomplished with a workstation or a workstation docking alcove. This element is frequently used for inpatient and prep/recovery rooms.

Decentralized Touchdown

- Nurses station - frequently done at patient and prep/recovery rooms

- Allows patient observation in a protected zone

- Relative cost: $

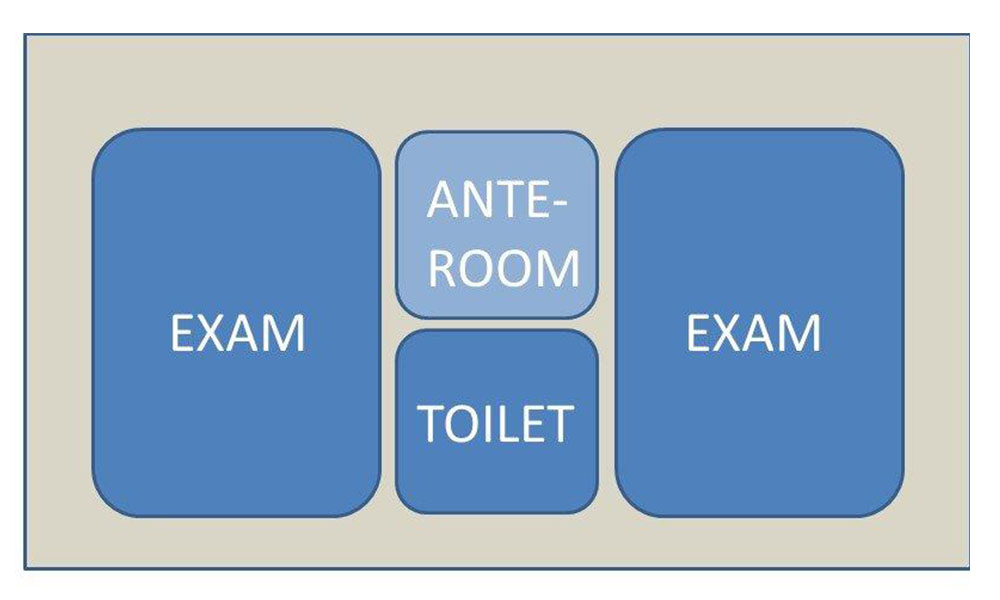

Bring back the anteroom –

Although it is no longer a code requirement, adding an anteroom to airborne infectious isolation rooms allows an intermediate zone to don and doff personal protective equipment.

Ante Room at Airborne Infectious Isolation

- Allows don/doff process in protected zone and minimizes exposure to others.

- Relative Cost: $$

Dual headwall –

Configure headwall outlets in exam and treatment spaces such that they can be readily adapted to treat two patients. Doubling up of non-infectious or non-critical patients would allow more patients to be treated.

- Allows comingling of less acute patients to accommodate surge

- Relative Cost: $$

Increase corridor width -

Increase the width of corridors at the ambulance entry and other critical junctures to allow staging of additional equipment and stretchers during surge events. Wider corridors in select areas provide ample space for staff to pass without physical contact with stretchers or supplies lining the corridors. Also, the enlarged corridor can be subdivided with sheeting to segregate clean vs. dirty traffic in extreme situations.

Relative Cost: Marginal

- Sub-divide waiting areas and minimize their use - Decentralized waiting areas, in smaller groupings, allow more social distancing which reduces infection spread. Operationally, staff can escort all patients to exam rooms as soon as possible – limiting their exposure to other patients.

- Relative Cost: $$

- Include staff shower facilities - Although shower facilities are only required for support of surgical staff, front line workers should not need to worry about transmitting virus particles on their clothing when they leave.

- Provide equipment storage – Include space for emergency supplies or ancillary equipment in (or immediately adjacent) to the department to avoid unnecessary in/out traffic and mitigate the potential for cross-contamination. Items stored in the department could be supplemented via remote storage areas and modified to support immediate needs.

Heating, Ventilation, and Air Conditioning (HVAC) Considerations

Of all building infrastructure systems, the HVAC system has the most significant impact on containing and managing infectious diseases. Engineering tools to manage airborne particles include airborne infection isolation rooms (AIIR), 100 percent exhaust, a higher number of air exchanges (12 air changes per hour vs. 6), and High-Efficiency Particulate Air (HEPA) filtering. Current health codes only require negative room pressure and no recirculation of air only in specific areas of the ED, such as the waiting area, triage, isolation rooms, and decontamination spaces.

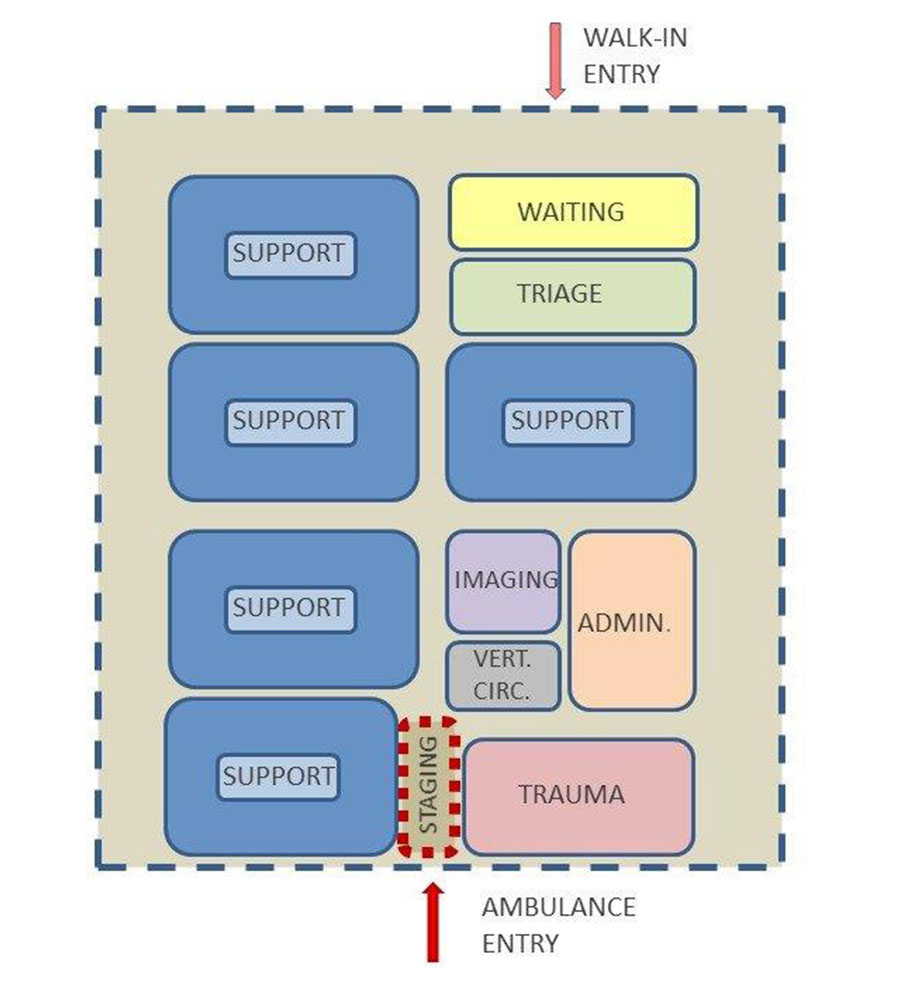

Code Minimum Zones for Negative Pressure -

Waiting, triage, airborne infectious isolation rooms (AIIR) are required to have negative pressure and 100 percent outside air.

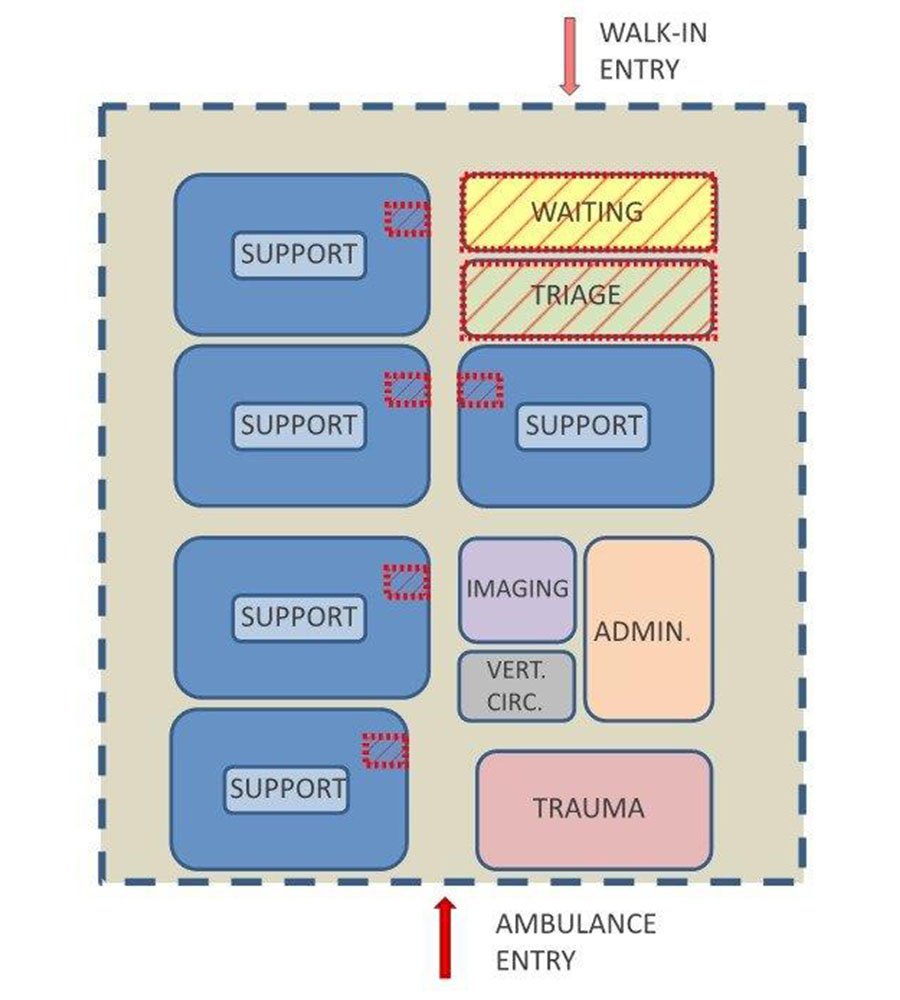

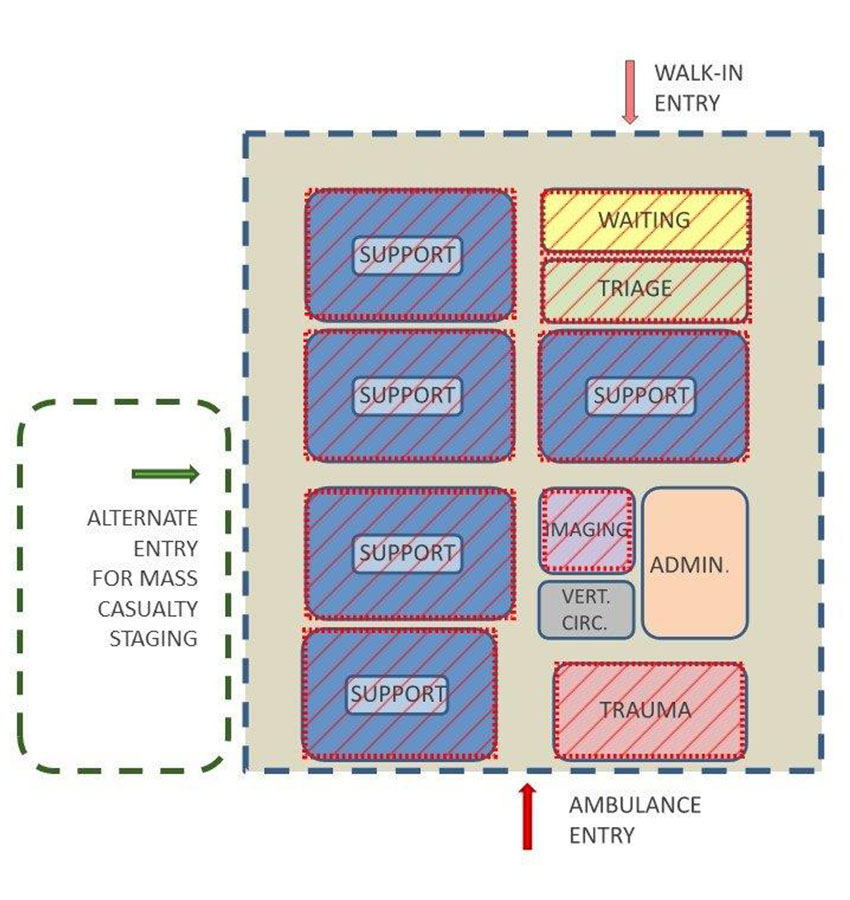

For new projects in design, the hospital may consider an increase in the areas with negative pressure capability. Depending on the size of the department, some or all pods could be designed with negative pressure and exhaust capability. Air intake louvers, coil capacities, and associated pipe sizes would likely need to increase along with capacity at the central system. The price premium for additional negative pressure could be significant – depending on the size of the project. The air system would run at the code required minimums during normal operations and facility staff could convert to negative pressure mode by adjusting the building automation controls to 100 percent exhaust.

Expanded Zone for Negative Pressure -

- HVAC system with Pandemic Mode can increase zones of negative pressure.

- Alternate entry allows a portion of the ED to be segregated for surge while the remainder operates without impact.

- Relative Cost: $$$

Although the strategies outlined above are for pandemic situations, many of these policies can help manage other types of mass casualties and emergency. For instance, pod layouts with card access allow locking down different areas during a security breach.

A layered, systematic approach to managing a disaster event provides the highest level of protection for both the patient and staff. During non-surge time, many of these elements recede into the background and do not impact normal operations. However, during surge events, staff can quickly adapt to extreme conditions with minimal facility modifications.

While the Facility Guidelines Institute (FGI) addresses mass casualty events, the code provides only a basic framework of minimum requirements. The current COVID-19 experience will undoubtedly prompt many discussions about increasing the stipulations in future editions to include those of greater magnitude. Each facility will need to assess their threat response relative to their situations (urban vs. rural location, size, and cost implications).

Assuming unpredictable events will continue to impact capacity, the current COVID-19 situation presents planning considerations to manage other types of surges - whether they be naturally occurring, such as Hurricane Katrina or human-made, such as the terror attacks of 9/11.