The Imperative of Inclusive Design & Integrating Disabled Voices into Your Process

In our recent work, EwingCole’s Design Research Team has teamed with clients who are seeking ways to remove barriers that have historically created challenges for people with a disability. The Principles of Inclusive Design (ID) have often been used as a starting point to assess how supportive or not, the environment truly is.

According to a 2022 Center for Disease Control (CDC) report, 15% of the global population has a disability. In the US, approximately 25% of the population has a disability, and 40% are older adults with intersecting disabilities.

Ensuring equal access to healthcare, buildings, and information for people with disabilities is a crucial factor in improving health outcomes. Incremental, realistic approaches to designing accessible environments foster a culture of inclusion and have a direct, positive impact on health outcomes.

According to Emily Ladau, a disability rights activist, writer, and speaker, “Accessibility is about making things more equitable so that disabled people have the same opportunities and support to thrive as do non-disabled people. It’s about removing barriers to participation, engagement, and understanding so that all people, regardless of ability, can experience the world around us to the fullest extent possible in ways that work for our minds and bodies.”

In our recent work, EwingCole’s Design Research Team has teamed with clients who are seeking ways to remove barriers that have historically created challenges for people with a disability. As a framework to measure personal experiences against, the Principles of Inclusive Design (ID) have often been used as a starting point to assess how supportive or not, the environment truly is.

Principles of Inclusive Design

Applying the principles of ID creates an inclusive society that acknowledges human diversity, promotes independence, ensures equality and social inclusion on equal terms, and promotes respect for every person's needs. However, inclusion does not just deal with physical accessibility and architectural barriers; its definition includes understanding how people behave, socialize, live in, and access space.

Why it Matters in Healthcare

Accessibility in architectural design is crucial, especially in healthcare facilities. All patients should benefit from the design regardless of their abilities. Yet, studies reveal limited adoption of inclusive design, possibly due to the challenge of catering to diverse needs. As a result, people with disabilities are less likely to receive comprehensive preventive care, annual dental visits, diagnostic imaging, and recommended cancer screenings and are often excluded by the healthcare system from health promotion efforts in the community.

Raising awareness is key to promoting an inclusive mindset among architectural professionals and healthcare providers.

Survey data from a recent EwingCole research study showed that all patients with different types of disability and their caregivers, with a percentage ranging from 21% to 53%, had complaints about inaccessibility. The subsequent complaints from patients with vision impairments came from unsuitable flooring (17%) and wayfinding (9%). Patients with cognitive and hearing impairments were among the vulnerable groups that had problems regarding wayfinding, with 16% and 9% of complained cases, respectively.

The study’s results demonstrate that the built environment of healthcare facilities is often incompatible with patients’ needs related to different types of disabilities and with best practices for promoting the inclusion of all body types (while thorough, the list below is not exhaustive).

Mobility

- Difficulty walking or climbing stairs

- Paraplegic

- Fatigue

- Limb Difference

- Lost Limb

- Person of Size

Cognitive

- Difficulty concentrating, remembering, or decision making

- Difficulty living independently (doing errands alone)

- Neurodiverse

- Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD)

- Dyspraxia

- Dyslexia

- Dyscalculia

- Autism Spectrum Disorder

- Attention Deficit Hyperactive Disorder (ADD/ADHD)

- Dementia

- Bipolar Mania

- Long COVID

Vision

- Blindness

- Difficulty Seeing

- Color-Blindness

- Limited Sightedness

- Loss of Central Vision

- Loff of Peripheral Vision

- Blurred Vision

- Generalized Haze

- Extreme Light Sensitivity

- Night Blindness

- Refractive Errors

Auditory

- Deafness

- Difficulty Hearing

- Limited Hearing

- Sensorineural Hearing Loss

- Conductive Hearing Loss

- Mixed Hearing Loss

Obstacles and Barriers to Disabled Persons in Healthcare Facilities

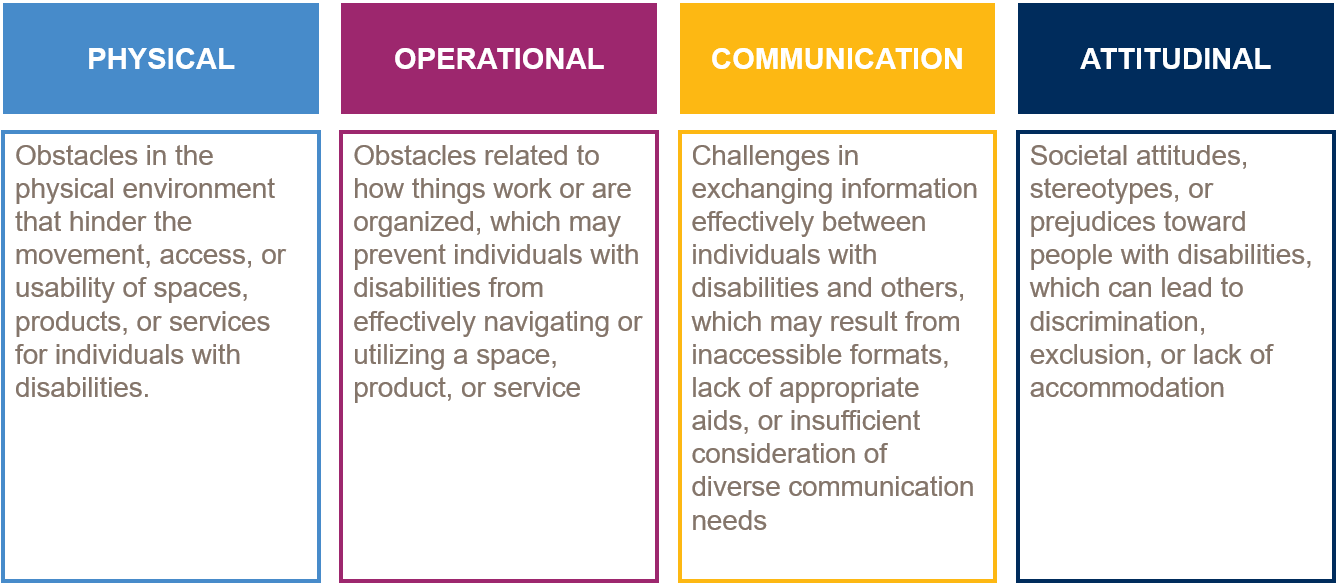

Inaccessible facilities, communication barriers, and discriminatory policies hinder healthcare access. Merely adding ramps and grab bars isn't enough; physical, communication, attitudinal, and operational obstacles must be tackled. Embarrassment over needing extra assistance can undermine feelings of independence. Moreover, issues like prejudice and poor accessibility heighten the risk of secondary health complications for people with disabilities.

Let’s identify some of the barriers in the built environment that affect access to quality care and try to understand the importance of how different factors interact.

Operational Barriers

- Long wait times

- Staff training

- Appointment time availability

- Patient transportation

Physical Barriers

- Geographic inaccessibility

- Barriers for wheelchair/walker users

- Barriers to those with limited mobility

- Poor lighting

- A lack of clear signage

- Inaccessible diagnostic equipment such as X-ray or mammography equipment

Communication Barriers

- Low awareness of health services in the community

- Inaccessible tools: Health information, appointment times, and prescriptions may not be accessible

- Making health information easy-to-follow formats, including plain language, pictures, or other visual cues.

Attitudinal Barriers

- Stereotyping

- Perception of inferiority

- Pity

- Ignorance

- Spread Effect

- Backlash, resentment

- Denial

How Do We Implement Inclusive Design into the Process?

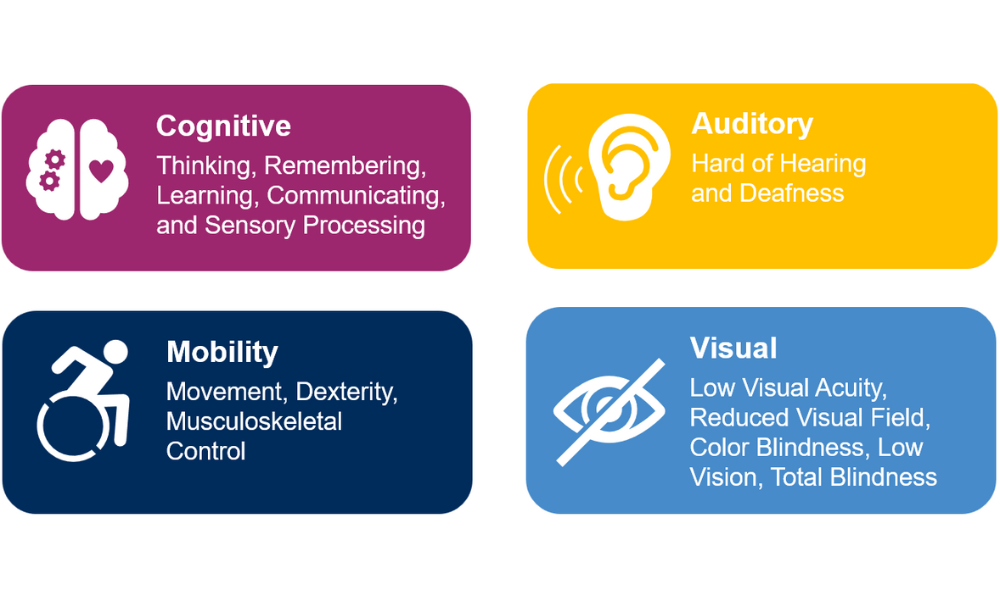

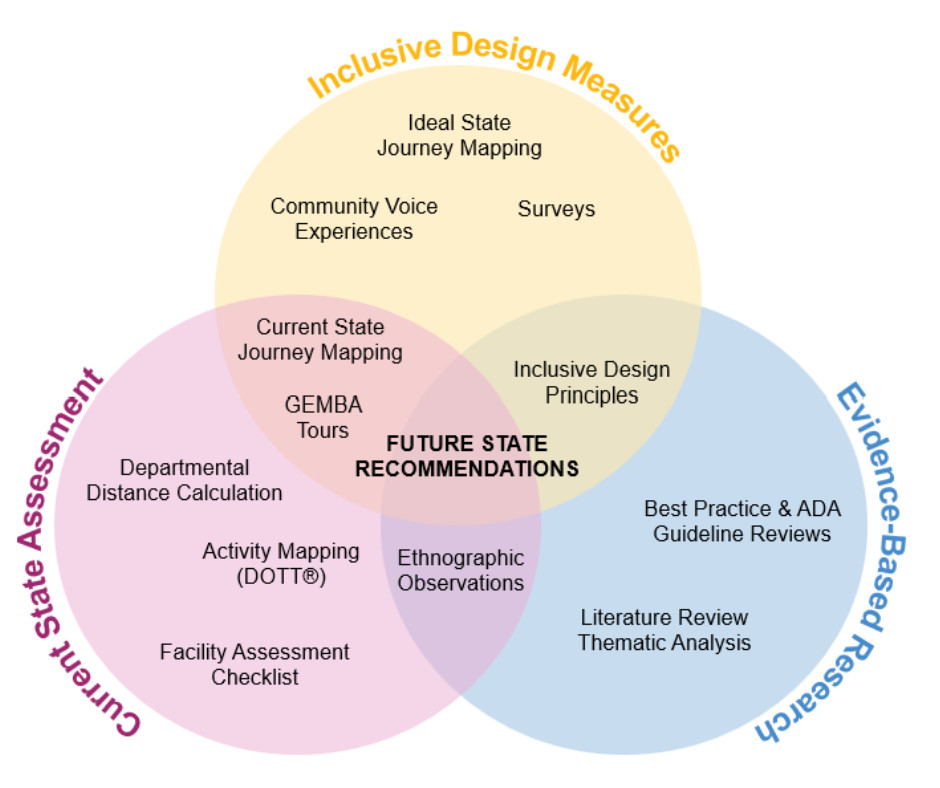

In the 1990s, the disability rights movement adopted the motto “nothing about us without us” as a call to action demanding people with disabilities be fully included in the decision-making regarding what impacts their lives. For this study, we adopted a collaborative, mixed-method approach to assessing and designing with a diverse representation of people across a spectrum of disabilities, including mobility, visual, auditory, and cognitive disability. Our team collectively represented patients, hospital staff, as well as people within the surrounding community. This approach not only works to understand a diverse perspective based on disability identity but also how it relates to personal use experience.

Our process explores various barriers that imply ignorance and foster non-participation and exclusion, as well as accessibility that enables participation. We analyzed survey data and conducted time and motion observation analyses to understand user trends and patterns using our proprietary tool, DOTT. We organized qualitative data from interviews, workshops, surveys, and observations into key themes and categories.

Solutions Through Built Environment and Process Design

When designing, renovating, or furnishing facilities, healthcare providers should investigate and ensure that they adhere to all accessibility requirements and accommodate the needs of a diverse range of populations.

We advocate for a direct approach that directly engages with stakeholders, including individuals with disabilities, in meaningful ways and throughout the design phases, ensuring that stakeholder voices are well-represented and integrated into designs. It says to them, "Your input is invaluable in this collaborative effort."

Designing an inclusive facility for a specific community requires special attention to their unique needs. Design solutions must address accessibility, privacy, flexibility, and navigation barriers commonly faced by patients with disabilities. This approach ensures the facility is truly inclusive and meets the community's diverse needs. Designers should consider the following:

Gender and disability: Even though issues faced by men and women with disability are almost equally the same, they have different experiences of marginalization and social exclusion. For example, women with disability often experience additional discrimination as a result of gender inequality.

Lifecycle approach: The healthcare needs of people with disabilities change throughout their lifetime, day by day, and even throughout the day. This is why providing options is so critical. It enables individuals to choose how to interact with the world around them, fostering environmental empowerment and enhancing their sense of belonging. By offering choices, we support their autonomy and adaptability, creating an environment where all can thrive.

Ethnic, minority, and other marginalized communities: Remove any barriers for marginalized communities related to the status of the communities, such as refugees.

High-level design considerations:

- Travel distances - Consider opportunities to reduce travel distances to the point of care and reduce the burden of travel distances. Create respite and information stations along paths of travel that include inclusive tools, such as mobility aides, and inform travelers of their anticipated distance to enable them to choose how to navigate the route.

- Communication - Focused study on campus signage design, placement, and use to address inclusive updates. Key elements include color, contrast, font, size, simplicity, repetition, location, international symbols, icons, pictures, Braille, and low visibility audio/verbal/tactile options. Inclusive signage should feature significant, raised letters and icons with solid contrast, presenting information in text, visual, and tactile formats to accommodate diverse processing and language skills. The use of audio announcements is also beneficial.

- Check-in experience - In addition to the above communication measures, ensure access to translation and mobility services upon arrival. Provide multiple counter heights without obstructions at staffed desks, ensuring a clear line of sight for social interaction between staff and visitors.

- Elevators - Ensure adequate free space in front of elevators, proper door width, voice announcements, clear visual level displays, Braille buttons, and sufficient lighting. Designers should avoid metallic or shiny surfaces inside elevators to reduce glare for individuals with visual impairments.

- Main Lobby - Consider ways to shorten the distance from drop-off to check-in and provide wholly inclusive security and check-in measures at this location (for example, using swing gates instead of turnstiles provides a more physically inclusive security measure).

- Use of Materials - Choose flooring finishes that contrast with walls to delineate navigation paths, aiding individuals with low vision in navigating spaces without bumping into walls.

- Bathrooms - Provide grab bars, large turning radii for mobility aids, automated door openers, and appropriately weighted doors. Ensure accessible reach and visibility to soap, drying functions, and full-length mirrors. Include adult-sized changing tables for caregivers of all ages.

Due to the project scope, our research specifically focused on how a person with a disability experiences a given environment. However, it is important to understand that inclusive design is also focused on providing equity and dignity across cultures, gender identity, personal differences, and preferences. Inclusive design recognizes that all people should be able to navigate their space and world without barriers. An include design process, is one that makes sure there is a diverse representation of experiences at the table.

Inclusive design, as a foundational principle, strives to create environments, products, and experiences that accommodate the diverse needs of all individuals, regardless of their abilities or disabilities. While addressing physical accessibility beyond the ADA requirements—which represent the bare minimum but not necessarily the optimum—we are also considering barriers across cognitive, visual, hearing, and physical domains. This broader approach helps us understand the full implications of inclusive design. It underscores the importance of considering communication and attitudinal barriers, emphasizing the need for holistic approaches to create truly inclusive environments. In essence, the study serves as a testament to the transformative potential of inclusive design in shaping environments that prioritize equity, dignity, and participation for all individuals.