Returning Daylight to the Hall of Fossils

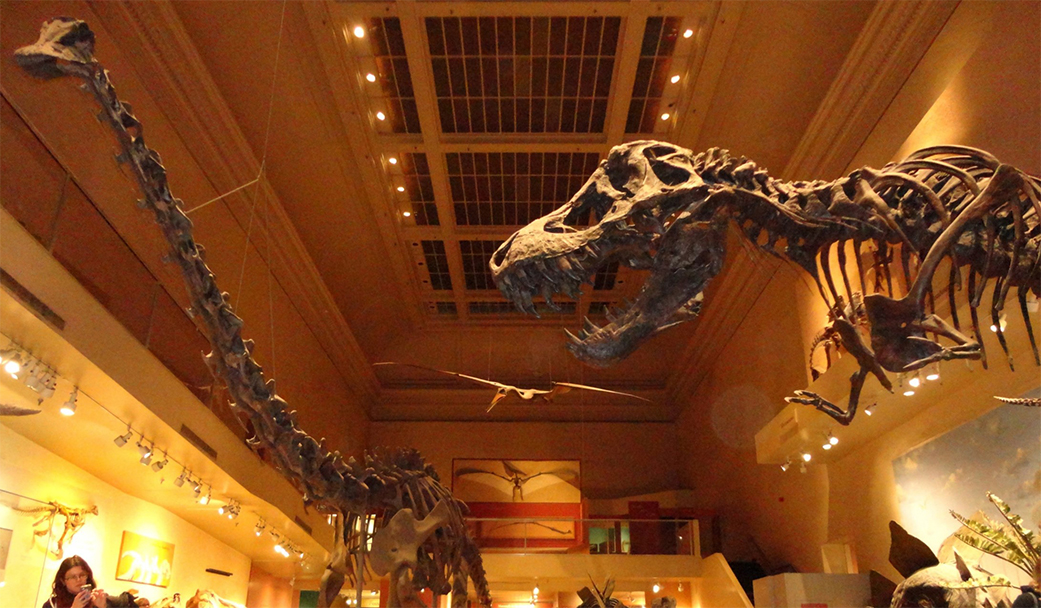

Since it’s 1910 opening, the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History’s main halls were bathed in natural light, showcasing its prehistoric specimens in full view. The skylight was sealed after a series of renovations between the '60s and early 2000s, leaving some of the museum’s most notable specimens in the dark. Our lighting designers saw the potential in its reopening.

Some of the most successful natural history museums in the United States are home to amazing collections of dinosaur and prehistoric fossils. Their remains are a window into the chasms of Earth’s history that spark the imagination of both scientists and the curious public the world over. As designers, we have a unique opportunity to help museum curators and scientists share these discoveries with millions of visitors.

Managing these light sources is critical to the aesthetic of the exhibit design, the care of the priceless collection materials and the integration of museum character.

Since it’s 1910 opening, the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History’s main halls were bathed in natural light, showcasing its prehistoric specimens in full view. The museum’s skylights remained prominent features of the structure throughout most of the 20th Century.

Since the 1960s, however, the David H. Koch Hall of Fossils – Deep Time, formally known as Fossil Hall, had undergone several significant renovations, which drastically altered its appearance and concealed the Beaux-Arts designed hall’s enormous skylight, leaving some of the museum’s most notable specimens in the dark.

When planning and designing the latest renovation of the space, it was decided to “uncover” these skylights and return a strong sense of daylight to the historic gallery. Managing these light sources is critical to the aesthetic of the exhibit design, the care of the priceless collection materials and the integration of museum character.

To do this responsibly, several things needed to happen. We first identified what portions of the specimens were vulnerable to light damage. These specimens require care to preserve their biological and geological material for research and future generations of museum visitors. We also looked at how to create an environment where the public can enjoy some of the Smithsonian’s most important pieces. Lighting is a critical consideration for showcasing the scale of the animals, the intricacy of their structure, and their context within a distant world. Finally, we identified a strategy to reduce energy use. The project was a collaboration between lighting designers, engineers, architects, exhibit designers, conservators, collection managers, facility managers, and curators.

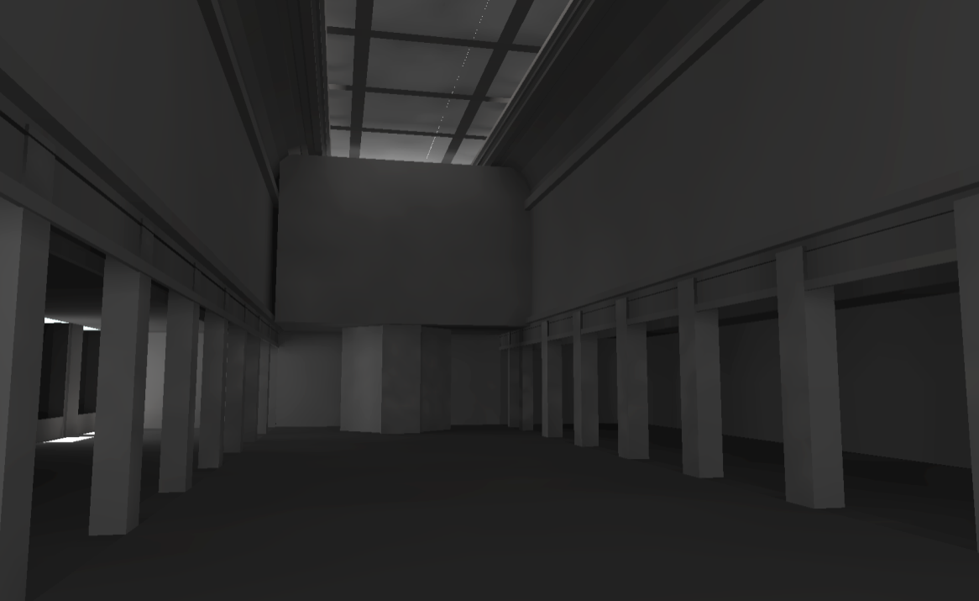

Since light was to be a prominent design element of the restoration, we needed to understand the potential impact of daylight on the specimens. Using a complied list of resins, polymers and solvents typically used in museum mounting or specimen conservation efforts, we were able to analyze their sensitivity against varying light levels. That early light modeling and material investigation helped set the stage for managing light levels throughout the design and construction phases.

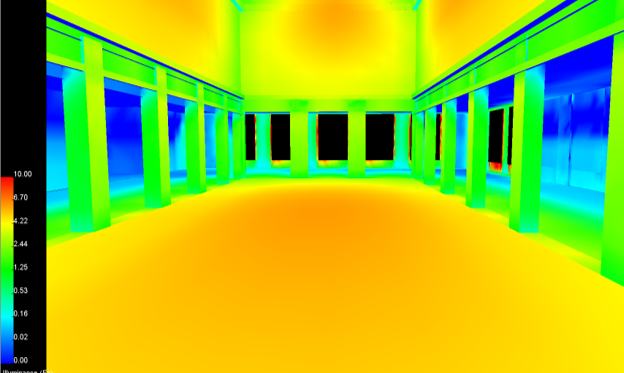

The models allowed our team to determine what other materials or tools we had at our disposal to protect the specimens. Light levels allowable through the design were set during the feasibility study based on existing light levels within the Smithsonian’s sister halls. The design team determined that a maximum of 10 footcandles (FC), or 100 lux, was enough to both illuminate the hall to adequately display the specimens while shielding them from harmful light radiation.

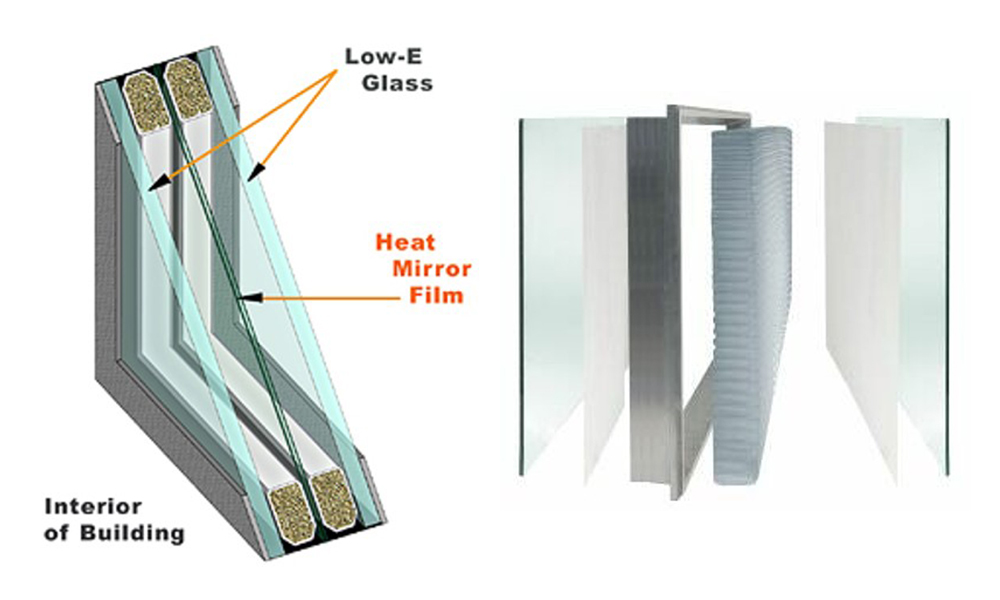

We ultimately turned to a glazing system containing an advanced aerogel nanotechnology that serves as both an insulator and light filter. We developed a custom skylight glazing unit utilizing the aerogel technology. This material contains 90 percent air and is one of the lightest and most effective insulating materials currently available. It both protects the biological and geological integrity of the specimens while regulating heat gain within the hall. This material mitigates both ultraviolet light and heat as it illuminates the gallery.

Prior to the renovations, the space felt artificial. It was almost a disservice to the story of the Earth’s broader ecosystem that the museum was trying to tell. Controlled daylight now floods the hall for the first time in nearly two decades, the prehistoric specimens below remain protected and the hall’s grandeur is restored. It’s soaring ceilings, ornate moldings and sheer scale are once again available for the public to enjoy.