How Designing for Everyone Makes Learning More Equitable

Our communities have always been diverse with unique needs. To ensure that everyone equitably benefits from their education experience, we continue to rethink how and where we utilize universal design strategies.

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), which last year celebrated its 30th anniversary, took a “civil rights approach” to addressing the needs of the physically impaired. Before the ADA, architects relied on a series of building codes that varied from state to state with no singular codified set of standards at the federal level. Differing regulations meant that a person with a physical disability might not have the same access to a public building in one state as another. The ADA ensured those individuals would have the same level of physical access to public buildings across the country.

Although these guidelines were a good first step, they are limited in scope and only consider physical mobility constraints. The impact they have made on the daily lives of hundreds of thousands of Americans is immense, but 30 years after the passage of the ADA, we must broaden our understanding of human needs and consider the myriad ways in which the built environment profoundly affects the daily, lived experience of each person.

Regulations like the ADA often lag the broader pace of social need. Simultaneously, social justice movements continue to shed light on issues that went largely unnoticed or were woefully disregarded, for decades. Since the passage of the ADA, we now, for example, have a deeper understanding of the effects of socioeconomic status on learning outcomes, there is a wider acknowledgment of the LGBTQ+ community and the challenges they face, and health factors beyond the visible – such as developmental or emotional disorders – are more widely understood. The question before architects is how do we address these needs through design and, especially the design of education buildings – considering that beyond the home, these spaces have a profound effect on an individual’s life trajectory? How do we ensure that no student is denied the full access to the amenities that can enhance their educational experience and enrich their lives, providing them with an equitable opportunity for long-term success? As leaders within the AEC community we continually seek to better understand diverse perspectives. We ‘raise the bar’ by being committed to finding innovative solutions through thoughtful, intentional, and inclusive design.

Universal design, as defined by the National Disability Authority, “is the design and composition of an environment so that it can be accessed, understood, and used to the greatest extent possible by all people regardless of their age, size, ability, or disability.” It takes a “human-centered” approach to design while respecting the user’s dignity, rights, and privacy.

The challenge is that universal program enhancements tend to be viewed as “nice-to-haves” rather than “have-to-haves.” Too often they are regarded as expensive solutions to a temporary issue, for example, when a student with a specific need resides in a building for a single year before graduating or moving on to another facility in the school system. As design professionals, who work under an ethical mandate to protect the health, well-being and welfare of the public, we take seriously our job to advocate for these enhancements to be the norm and not seen as luxuries. Our responsibility is to demonstrate the benefits of these program improvements, which is why we share how some of our universal design solutions, implemented across multiple institutions, are revolutionizing how students interact with the built environment and shaping their experiences.

Subtle Design Shifts the Paradigm for Personal Care and Wellness

One in four American adults today are living with a disability, according to United States Census Bureau data from 2016. The Census Bureau defines the disabled as someone living long-term with a physical, cognitive, or emotional disorder. Additionally, about one in six children aged three to 17 nationwide are diagnosed with a developmental disability. These include autism, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorders, blindness, and cerebral palsy, among others.

Roughly 246,000 of people with disabilities in Philadelphia – the largest population of the U.S.’ ten largest cities. The faculty and students of Penn Dental Medical (PDM) at the University of Pennsylvania have a unique view of this circumstance. The PDM Division of Community Oral Health provides an academically based service-learning program forming the framework for faculty and students to “expand community engagement in the Philadelphia region with patients traditionally underserved by dentistry, such as low-income adults and children, including preschool and school-age children, elderly, and those patients with medical complex conditions.” Those with severe physical, cognitive, or emotional complications have difficulty receiving routine dental treatment, leading to further compounding of both dental and other health issues. Alzheimer’s patients, those sensitive to light or sound, or stroke victims often can’t receive treatment at a standard dentist’s office. In these instances - even while treating the most routine dental procedures - many require anesthesia in a clinical setting, further stressing patients and stretching resources.

After nearly 40 years in dentistry, Penn Dental’s dean, Mark S. Wolff, DDS, PhD, believes that you can manage almost anything in your office with adequate training and suitable space. It’s this philosophy that drove the creation of Penn Dental’s Personalized Care Suite, a teaching facility designed to accommodate patients with any degree of dependency and provide specialized training to the next generation of dental care professionals.

Through various universal design elements, the PDM Personalized Care Suite can support both the needs of patients and a novel teaching curriculum. A variety of subtle design elements create an ideal and fluid environment for patients and students:

- A ribbed resilient flooring strip laid into the vinyl floor establishes a tactile wayfinding route: guiding patients into an open reception area and safely to each exam room in the facility. This tactile track allows those who are visually impaired to ‘read’ the layout of the space and guides patients directly to braille room signage at each location.

- Six open operatory bays and six individual exam rooms provide for varying degrees of mobility, privacy, light, and sound. The operatories are outfitted to maximize flexibility while keeping ergonomics and clinical safety at the fore.

- Three exam rooms are provided with Hoverchair-style dental chairs to accommodate a wide range of care delivery modalities. An easily moveable, tilting wheelchair lift also negates the need for patients to transfer out of their own chairs.

- Mobile caregiver seating is included in exam rooms, as dependent patients are often accompanied at appointments.

- The layout of dental utilities (Air, Water, Nitrous, Vacuum) was designed directly with Dr. Wolff to provide maximum flexibility, allowing dentists to reorient their workspace and deliver care as suits each patient.

- Quiet Room wall partitions are built with increased ability to dampen sound transmission. This room has color and brightness-adjustable lighting along with solar and black-out shading that provides a comfortable environment for those with sound, light, and noise sensitivities.

- A large exam room with oversized doors and direct access to the building’s public circulation corridor to accommodate a patient in a stretcher or hospital bed, who may be uncomfortable in a public waiting room environment.

The universal design elements within the Personalized Care Suite are fluid in that they are easily applicable to a multitude of learning environments. Everything from variable lighting, tactile wayfinding, a deeper study of ergonomics and flexibility, to quiet rooms and increased controls for privacy can be repurposed for other academic or healthcare settings. The common denominator among these design cues is asking early and often what all bodies need from a space to experience greater levels of comfort, ease and dignity.

Changing Room Facilities and the Impact of the Gender Binary in Schools

In 2014, Gavin Grimm, a transgender student at Gloucester High School in Virginia, was barred by school board policy from using his preferred restroom within the school following the complaints of parents and the community. A lawsuit filed by the ACLU argues "the bathroom policy is unconstitutional under the Fourteenth Amendment and violates Title IX of the US Education Amendments of 1972, a federal law prohibiting sex discrimination by schools." The case was brought before the US Supreme Court and then sent back to the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals, where the policy was ruled unconstitutional.

Non-conforming Bodies - People of different ages, races, genders, or disabilities who belong to marginalized communities who are frequently overlooked by the discipline of architecture.

The five-year court battle launched a national debate over trans youth and school bathroom policy, which continues today. The national discourse pushed school administrators and architects toward finding solutions that address the needs of trans, non-binary, and intersex youth. New York-based architect Joel Sanders developed an interdisciplinary design approach and subsequent guidelines for abolishing sex-segregated bathrooms that reinforce the gender binary to accommodate “non-compliant bodies” or those often underrepresented in architectural expression.

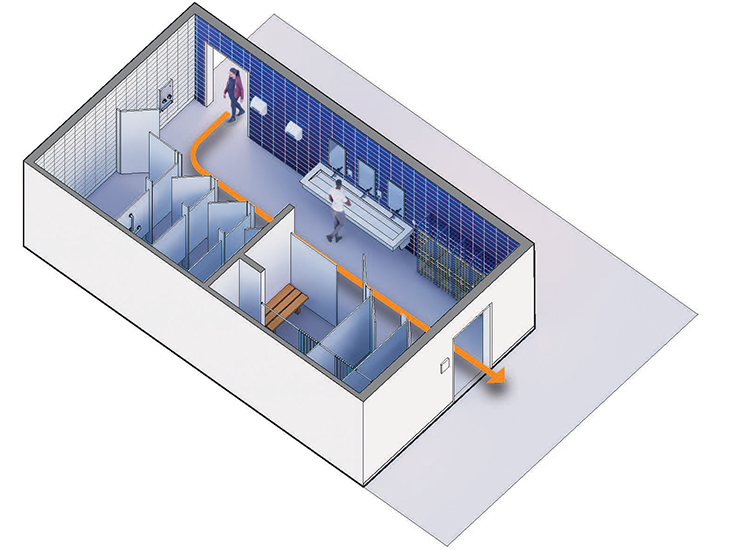

EwingCole adopted this same set of guidelines and principles when designing the William Penn Charter School (WPC) changing rooms for their new athletics and wellness center. The school’s administration took a progressive approach to their building design and sought to accommodate students of all genders and identities.

WPC’s visiting student changing facilities are completely genderless, referencing Sanders’ guidelines. Sightlines and ease of access are the two most important components. Increasing safety and negating potential bullying concerns are top priorities. To achieve this there are no blind corners or dead-end spaces, and there is an exit on either side of the room. The toilet stalls and showers double as private changing rooms, providing separation between wet and dry areas. The stall doors are also floor-to-ceiling, maximizing privacy.

This model brings several benefits for LGBTQ+ students and the entire building population: it optimizes space usage as well as reduces bullying, harassment, and intimidation. Their implementation creates a more inclusive environment with as many, if not more, practical benefits. This inclusive model is proving to be cheaper when local jurisdictional code allows for consolidation with gendered facilities. Apart from a few cities, most municipal codes and regulations require gender-segregated restrooms, so genderless bathroom/changing room facilities should be advocated for as part of the jurisdictional approval process.

Redesigning the Audio-Centric World

From door knockers and phones ringing to car horns and fire alarms, our world is designed around sound. However, for those without the ability to hear, particularly those who were born without it, the perception of sound is merely additional to the senses; not a deficiency of sense.

It’s through this lens that researchers and administrators at Gallaudet University derived the early concepts of Deafspace - an approach to architecture informed by the unique ways in which the Deaf perceive and inhabit space. Even now, they see the term as limiting because the Deaf lead a sensory-rich life, and Deafspace is about creating environments that appeal to each of these senses in a meaningful way, not one taking priority over another.

When EwingCole was tapped to design the Laurent Clerc National Deaf Education Center, a residence hall for students attending the Model Secondary School for the Deaf (MSSD), our designers discovered several commonalities between the needs of Gallaudet’s student population and contemporary design trends. Open spaces, abundant natural light, soft-edges and special transitions were among some of the broader elements students looked for in the design of their new residence hall.

Critical to the design was the implementation of well-lit, open spaces. This meant wider hallways and stairwells with abundant light sources that aid in visual communication or American Sign Language (ASL). Mechanical noise from an HVAC system, for example, was another consideration. It can be distracting at best or extremely bothersome at worst to the partially deaf, so limiting mechanical sounds around study and living spaces was paramount. Placement and soundproofing of these systems required careful and strategic consideration and planning.

Above all, the students needed a place to call home. The central communal gathering spaces included seating areas for large and small groups, sharp edges and corners were largely eliminated, and reflective material is strategically placed throughout, allowing students to have a full view of their surroundings always. These details eloquently blend within the space, resulting in a comfortable environment that nurtures the sensory-rich world in which the students thrive.

The Laurent Clerc National Deaf Education Center delicately exaggerates a number of design features we see in standard buildings today – like open spaces, abundant natural light, and soundproofing. When applied to a school or academic space, they not only assist the deaf but can also provide comfort to the hearing, limit distractions, and create more open and communal environments.

Why should we be considering more, if not all, of these enhancements in our schools during initial phases of design?

- Every institution, regardless of zip code, will have students, educators, administrators and public users who, one way or another, will be limited by a non-conforming condition or disruptive forces from having full access to their educational spaces. We should be proactively planning to accommodate as many of those potential needs as possible.

- Inclusive design adds value. The more people who can find success through an institution’s facility, the more that institution thrives.

- Universal design signals to students, faculty, and parents that the school acknowledges social change and human need, and instills a greater sense of belonging, empathy, and community.

Many argue that we cannot design the perfect space for everyone, of every need, all the time. We disagree and would suggest that is our responsibility, and we are taking on the challenge. In the early stages of design, our architects take their cues from the community and its stakeholders; all stakeholders, not just the vocal or often over-represented majority. We encourage and empower everyone to tell their stories. We actively listen to gain a better, more nuanced, understanding of how the built environment impacts their daily, lived experience. This practice leads us to comprehensive, holistic, and common-sense solutions that benefit all. Understanding barriers of our society members’ experience is the first and most critical step toward developing comprehensive and inclusive design strategies that strengthen the social fabric.